Here is a quick video describing one of my favorite Scoring Zone patterns, called "BUC", which stands for Backside Under and Cross. A frontside receiver is called to run a Deep 6 (BUC tells him to alter his technique), and we use the NINER Advantage Principle to guide the passer to the thinnest part of the pass defense.

|

Because of the proliferation of quick crossing routes in this pass offense, there must naturally be some "counters" to prevent defenders from sitting on these stems. Also, 3x1 sets tend to get the defense "tilted" to the 3 receiver side. Here is a quick video describing one of my favorite Scoring Zone patterns, called "BUC", which stands for Backside Under and Cross. A frontside receiver is called to run a Deep 6 (BUC tells him to alter his technique), and we use the NINER Advantage Principle to guide the passer to the thinnest part of the pass defense.

2 Comments

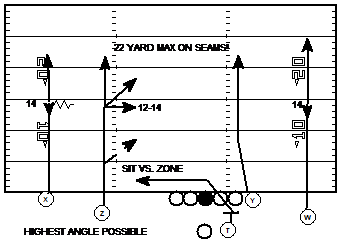

In my coaching iBook The Need for Change, I call for the need of mutual accountability on the part of coaches towards the players. Ninety-nine percent coaches are invested in their players emotionally; somehow, this dedication is at times lost in attacking defenses. An example of what I am talking about can be revealed below with the standard 4 vertical pattern. While it certainly has answers for multiple coverage possibilities, certain categories simply relegate the pattern to "settling" rather than attacking. For instance, vs. Man Free, the locked seam is of no use, allowing the Free Safety and extra underneath player to help on the seam read and back, respectively. Patterns should attack the full depth and width of the field - the elimination of targets by coverage allows the defense to level the playing field. Gripes are no good without a solution; below is a teaching video example of what I am talking about. We strive to give our players the ultimate pattern, regardless of the defense we will see. Here, the seam read is mated with a variation of the SNAG pattern on the frontside. Doing so has distinctive advantages: 1. The coverage is threatened to the fullest 2. It keeps patterns alive by giving the defense multiple threats that must be respected 3. It allows the offense to manage its strengths (ie - who is the good seam reader and free him up) Most of all, it allows the offense to be efficient with its pieces, allowing the offense to work techniques and routes that always keep the offense playing downhill.

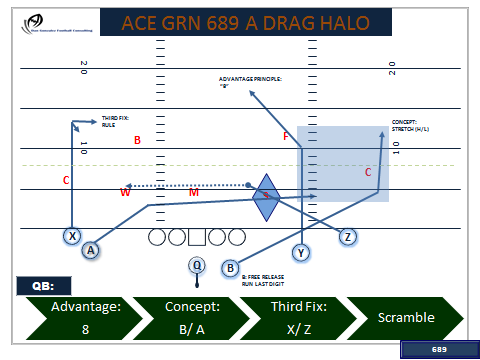

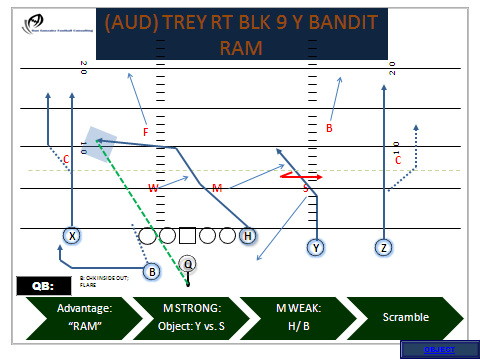

What is the beauty to be found in great systems? To me, it is not just the ability put up huge numbers. Rather, it is the ability to teach - it is the ability to take the complex and turn it into something very easy for players to execute. My consulting clients know that they can get a flood of updated information from me throughout the year. To be clear, these updates don't necessarily mean something new; instead, they are often "tweaks" to the existing. One such update (without necessitating a change in structure) is the revival of "Mesh" in this passing game. I learned the principle from Norm Chow when he was at BYU. Though the success of the pattern cannot be debated, few can argue the time commitment required to make it work the way Chow's BYU teams or the way Mummy/ Leach deployed their versions of the attack. Proving the flexibility of the system, we have found a very inexpensive alternative teaching method. In the route tree we used, we simply augmented the definition and technique of the "6" route: Even for younger players, the technique explanation is simple: run a 4 (hook), then run a 2 (short in). After all, 4+2=6. Running the "mesh drag" in this manner has several advantages: - The initial stem provides an additional quick throw vs. pressure - It is more effective vs. match up zone, as the hook stem is something a LB will drive on, and redirect to on the re-start - This vacates the area for the backside drag better than the traditional mesh - It is obviously less expensive than traditional mesh - The timing provides a Third Fix outlet on the backside From this simple adjustment, along with the stair step technique that is taught with standard drag routes vs. man coverage, one is able to assemble an exciting array of possibilities. This pattern has been extremely successful in 7 on 7 this summer, as it not only compliments the "471" pattern (seen here), but the weak side B wheel pattern as well. Another variation inspired by the checkdown techniques of Steve Spurrier's teams, combined with DRIVE, is shown here: How inexpensive is this tweak in teaching technique? My son's 7 on 7 team has been able to throw and catch both of these passes (along with Stick/Levels with RAM, 471, 220, and 09 A Badge) for scores in the last 2 weeks.

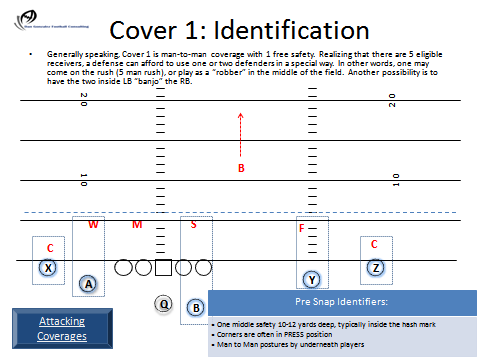

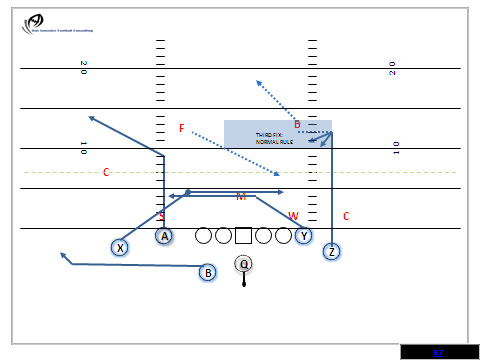

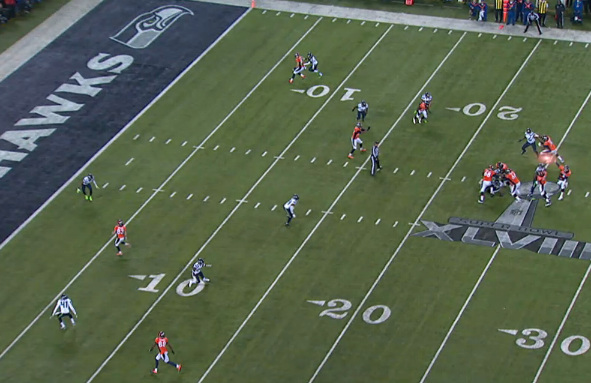

PS - days away from having my iBook available for purchase. Hindsight is 20/20. We know this, but we also know that those who do not learn from the past are doomed to repeat it. As I look back on the past Super Bowl, I am reminded of things I learned in a pro-style offense decades ago, yet can be forgotten with the preponderance of today's spread thinking. Going into the game, much of the talk of the Denver Offense vs. Seattle Defense conversation was the high percentage of "Cover 1" the Seahawks' defense would play. Many agreed that Peyton Manning's penchant for getting the ball out quickly would help negate Seattle's defensive prowess. Looking back, however, one wonders if this thinking helped play into Seattle's hands. In the diagram above, we have a vanilla interpretation of the Cover 1, which is defines as man to man with 1 free safety deep (also called "Man Free" in football vernacular). The corners can play press, off, or "bail" in order to disguise their intentions. There is always an extra underneath defender (the M in the diagram) who can blitz, wall off crossing routes, or simply be a pest the QB must throw around. More on that in a bit. Initial examination will call for getting the ball out quickly, on flat or drag routes -- often in some "mesh" configuration. Some forms of offensive thinking will depend solely on quick routes versus this defensive structure. Superior match-ups may allow for this, but the defense can counter vs. a limited arsenal, and pounce when they see a familiar pattern. The big hit on Demarius Thomas was proof of this: Cam Chancellor, the frontside safety (F), rolled down in a version of 1 Robber. His depth allowed to track the shallow and make a big hit. Further examination, however, shows Eric Decker WIDE OPEN on his in cut. Had the progression called for scanning INTO the in route, as we teach, he would have seen the open route, as well as seeing Chancellor because his eyes would start in front on the flag by A (Wes Welker) and swing into the route. Homer Smith introduced this idea to me years ago, and it still resonates today -- our eyes jump (or "saccade") from one spot to the other; carefully planned progression passing should take the passer to these routes not only so he can see the "danger" out in front. Navigation Tags, as described here, are primarily for helping with zone completions (a coach needs the ability to direct his player on every snap based on game and coverage situations); defeating man coverage necessitates maintaining all possible options on a pass play. As a collegian, the defense I saw every day in practice played press man on a majority of the snaps; here is what I know about beating man to man -- while rub/ mesh routes are great, there is no substitute for attacking with depth. The FLAG route might be the best of all routes vs. this coverage. However, a limited set of routes once again gives the defense an advantage. In another example, the Broncos are in the Scoring Zone. They have a Post/ Wheel combination to the left, with spacing/ comeback to the right. The defense shows Cover 1, then actually bails to a combo coverage, playing zone on the post/wheel side and man to man against Welker on the right side of the formation. Below, you can see the ball is already coming out -- and the potential danger awaiting. This is an example of why the ball coming out in the same rhythm (even quick rhythm) all the time is a potentially bad thing. If the only objective of the offense is to get rid of the ball quickly, this actually plays into the hands of the defense, as cover men are not stretched to the limits of their abilities. It simply takes less talent to cover for a short period of time. For this reason, deep ins/ outs are a MUST when defeating man coverage. Depth makes a man defender, no matter how talented, turn their hips and run. Even in this one-sided Super Bowl, the Bronco's positive plays came on deep crossing routes and ins/ and outs. Below, on the same play as above, look at the comeback route at the top of the screen. The ball being gone is irrelevant; the corner covering has no idea the ball has been thrown. Make no mistake - the game was, as they say in my hometown of Paris, TX -- "a whoopin''". The Seahawks were a more physical team, and the nature of the Denver running game didn't help, as it was too dependent on box counts rather than calling and running plays, regardless of the defensive look. Protection was a major issue, but the defense had as many pressures when in zone as they did in man; the coverage does not add time on a given play, just as adding a check-releaser (from 6-man to 7-man, for example) has no effect. Protection time can be gained with carefully programmed scan and help calls. The paradox was the plan of quick completions vs. what actually disturbs man coverage.

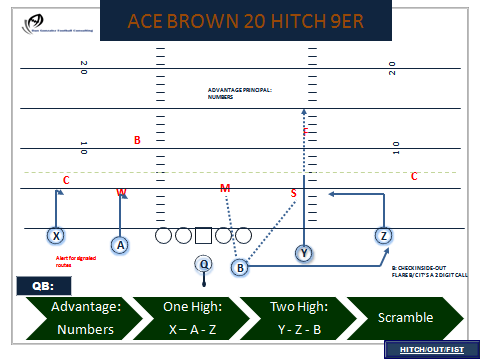

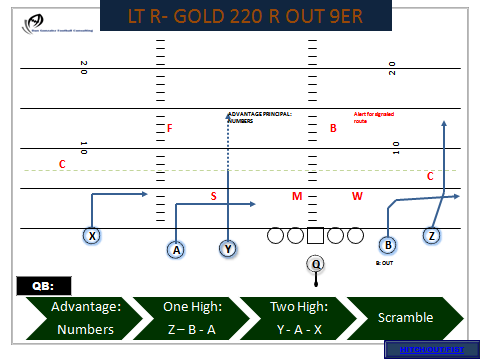

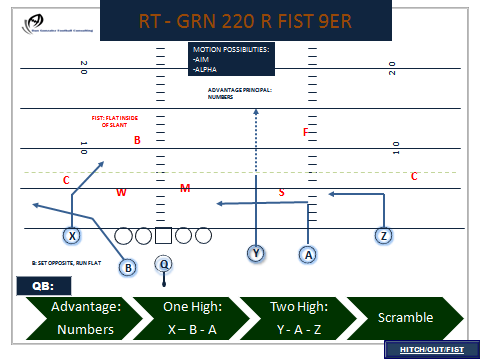

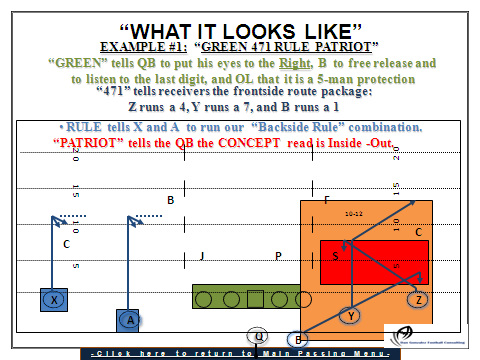

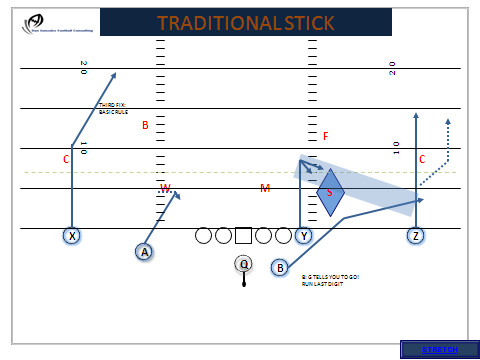

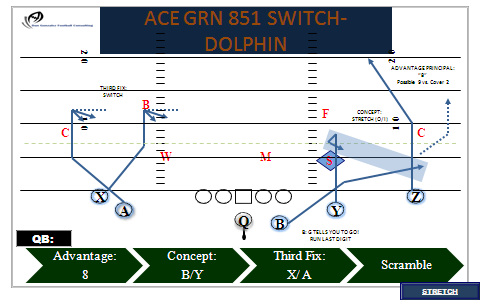

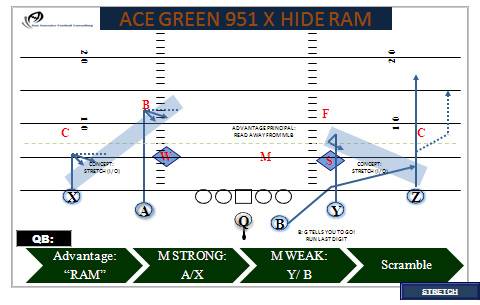

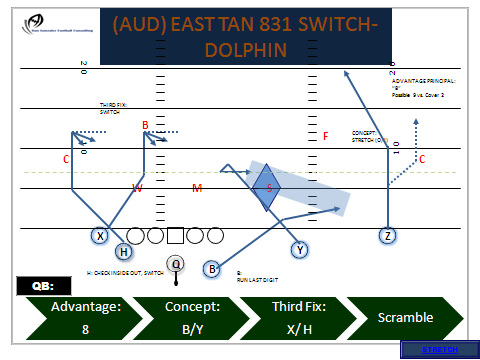

The premise remains: in attacking man coverage, explosive plays are a must, and are not always available when solely releasing the ball in quick rhythm. I have a few projects in the works, so my time has been divided. I have, however, received a lot of questions in regard to how the traditional QUICK game fits into the verbiage described in Recoded and Reloaded. So, here is a short write-up. First, in regard to how we CALL these pattern sides, they are NAMED routes that fit into the backside of the numbered frontside pattern. For those who are unfamiliar with our play calling system.....go buy the book. Just kidding. Below, you can see a diagram giving a brief explanation: The patterns are described just as in many systems: HITCH, OUT, or FIST (Flat Inside a SlanT): We tag these patterns with the NUMBERS (9ER) Advantage Principle, in which we have a pattern to attack single high or soft corners, and a default Cover 2 pattern to the frontside. We will plan our quick side to defeat single high, while the 220 pattern offers a solid choice vs. Two Deep. One benefit to the high school or college hash marks is the ease with which true two deep can be surmised: with the ball on the hash, as in the diagram above, the BACKSIDE safety (B) must play on or outside the hash in in order to be a half field player. Regardless of where F (front side safety) aligns, if B plays inside the hash, we will treat the alignment as single high.

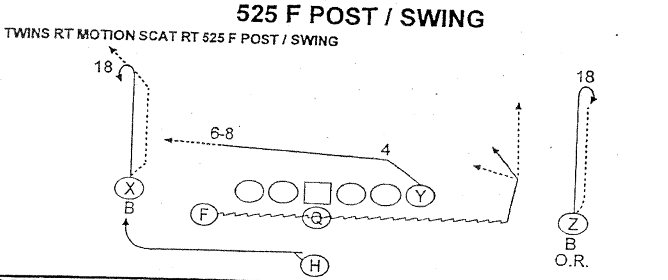

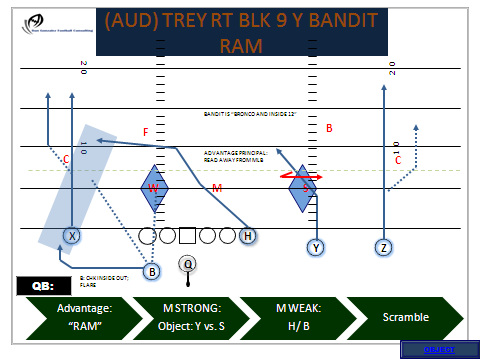

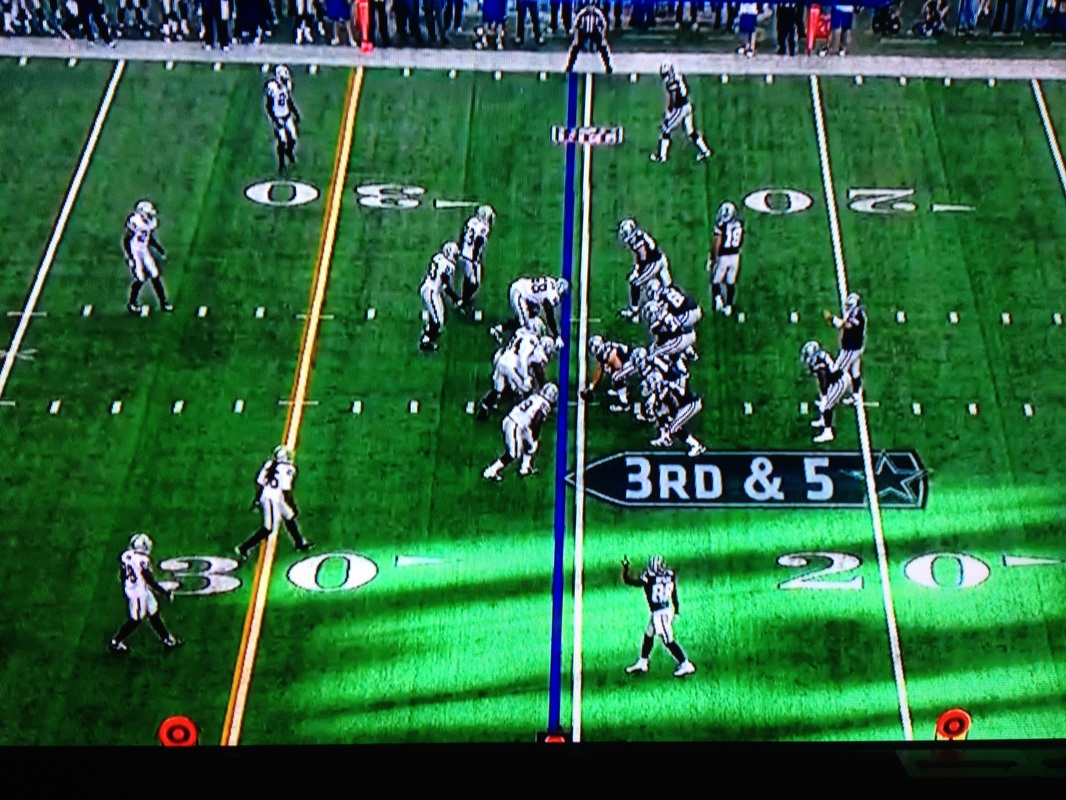

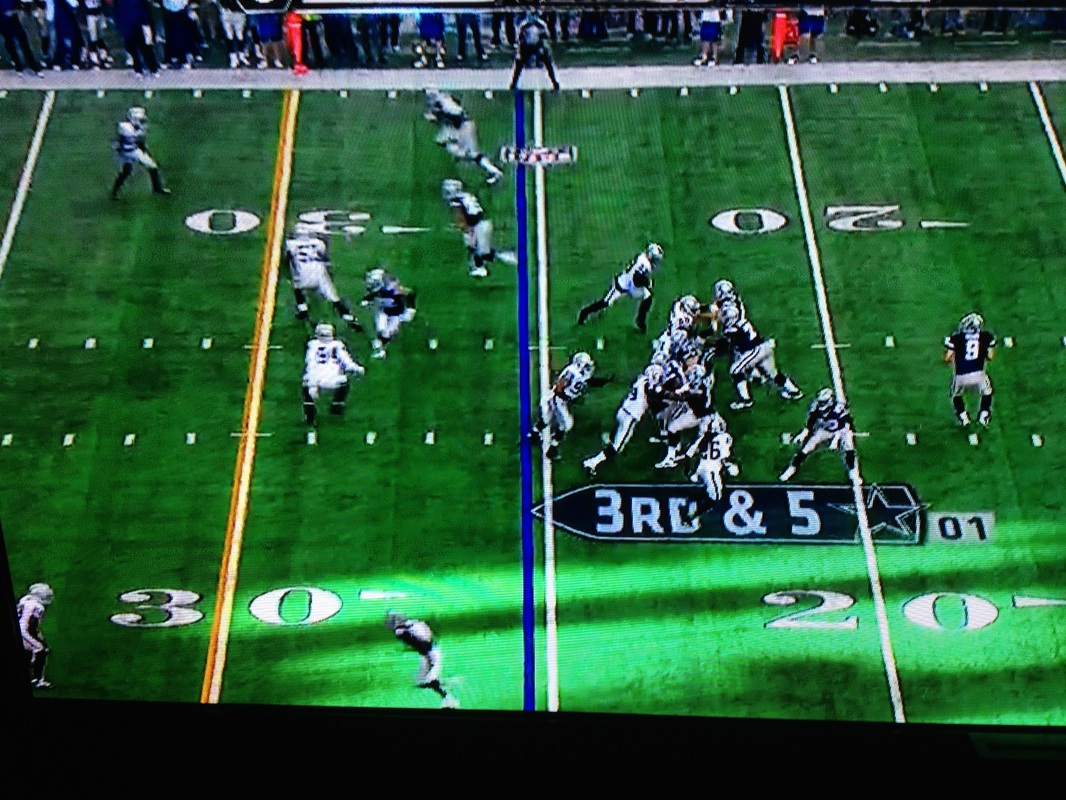

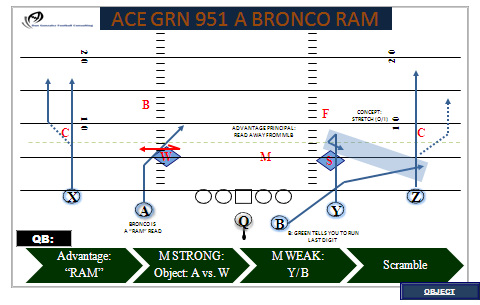

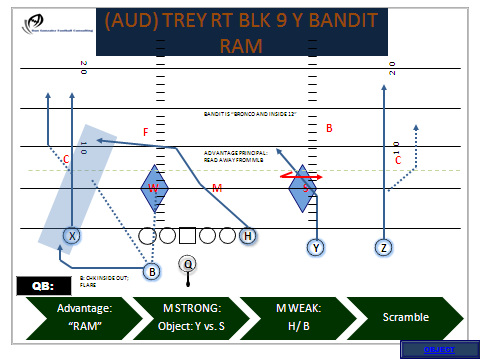

As a result, the QB's decision is simple and decisive: if the safety is inside the hash, he can count on single high principles to the tagged quick route; if he is on or outside the hash, he works the "220" pattern. The accountability falls to the coach to carefully plan boundary and field formational looks, but the work for the QB is clearly defined with an Advantage Principle that not only facilitates the quick game, but this offense's version of the Run N Shoot "Choice" route as well. This represents the most basic presentation for quick routes. Hope this helps! As one who is an admirer of the rhythm of the Zampese/ Coryell passing system (and I'd have to call you a communist if you weren't), one could say that few things in offensive football are prettier than the QB taking a rhythm drop, hitting a quick post as the receiver crosses the defender's face, and turning a short pass into a huge gain. A staple play of the system is SCAT 525 F POST; from Zampese/ Coryell to Turner to Martz to all the others who descend from this lineage, this play was sure to figure prominently in the play selection. While his predecessors switched personnel groupings to get the desired player in the F position, Martz added the ability to simply call 525 Z Post/ H Post/ X Post to give the play even more formation flexibility. Whether it was Faulk, Bruce, Holt, Az-Hakeem, or Proehl, Martz's Rams could dial up anyone to run the quick post. The play is designed to isolate the Post runner (hopefully vs. no short hole player) for a quick rhythm throw and catch. There are only 2 caveats: 1. The post runner is not to chop his steps -- this is an absolute in this offense in general 2. The post MUST cross the face of the man over him. If #2 DOES NOT happen, the passer hitches up, and swings his eyes backside, to the 3 man pattern created there. While the likes of Aikman, Warner, Fouts, and even Everett have shown the ability to do so, I would place this on the higher end of the spectrum, as far as degree of difficulty is concerned. As a solution, I offer BANDIT, which is a variation of BRONCO, the backside option route discussed here. Using the RAM advantage principle, the passer is able to assure a clean 1 on 1 to the slot; because of the option route rather than a "locked" quick post, there is a place to go with the ball even if the slot cannot get inside. On the Cowboys' first 3rd and medium last Thursday, Dallas dialed up 525 F Post. The Raiders had a 2 man disguise, only to come up with a Zone Blitz. The Cowboys have Miles Austin (#19) in motion to give him the release he needed as the post runner; however, the blitz forced Tony Romo to make a protection check at the line, delaying the snap and making Austin come to a set position: RAM rules dictate to throw away from rotation, but to throw TOWARDS a blitz, as we want our eyes on protection problems first. At the snap, the blitz is picked up; however, there is simply no way for Austin to get inside the LB (#53) buzzing out to him: From the QB's point of view, one can see the clear advantage of being able to hitch up, allowing the receiver to pivot out, as his access inside is denied, resulting in an easy completion: The corner will be cleared by the outside receiver, and the QB will not be stuck holding on to the ball with no place to go, as Romo was on this play. Furthermore, if the QB was treating this is straight zone because of the protection check (the zone blitz was nullified), the popular Y CROSS pattern is available for the passer away from rotation. Because the passer's eyes are on MIKE instead of locking in on the slot at the onset of the play, he can bring his eyes all the way our in front of the cross. The route technique affords the crosser the ability to defeat the match technique:

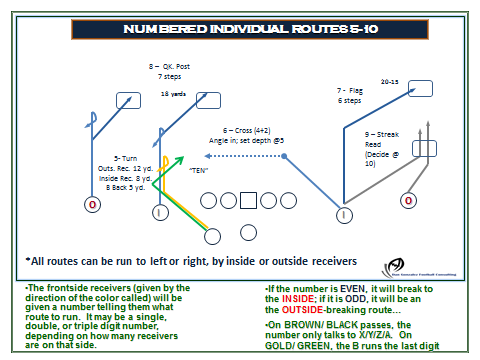

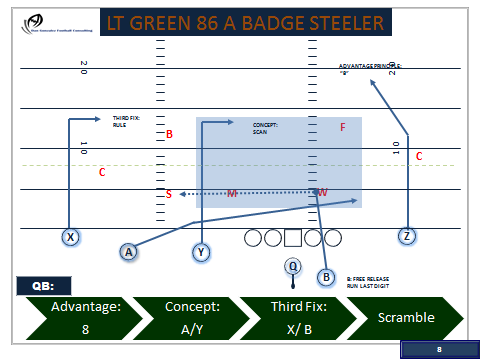

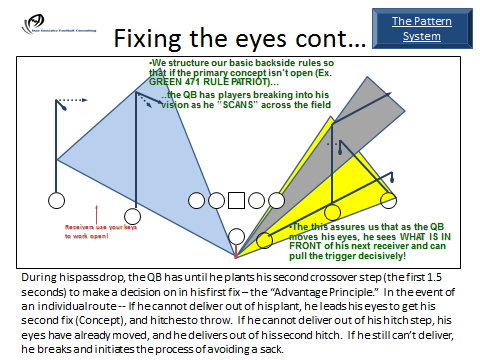

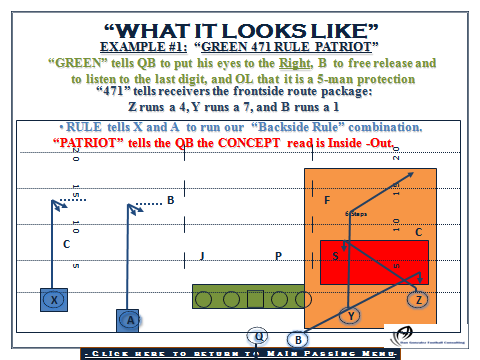

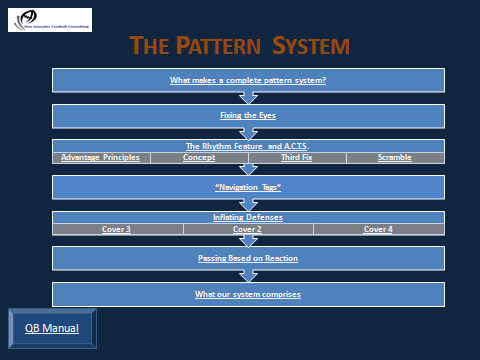

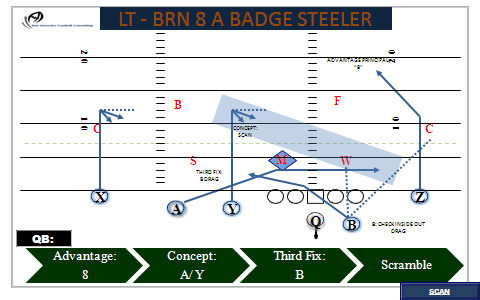

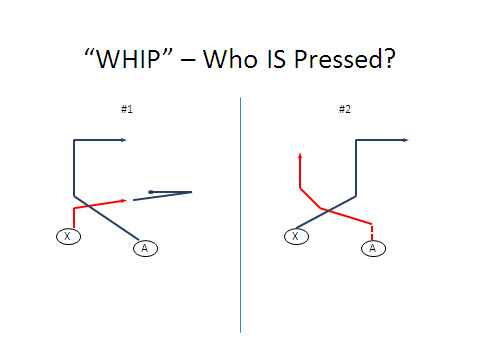

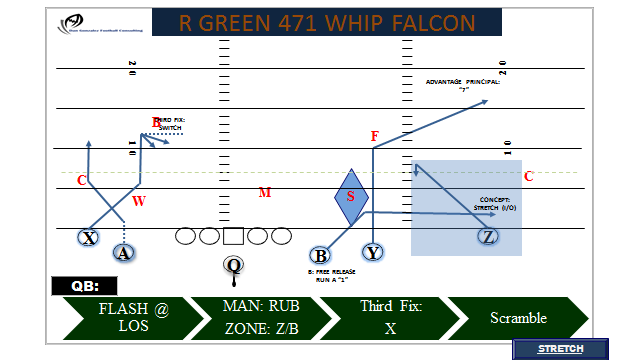

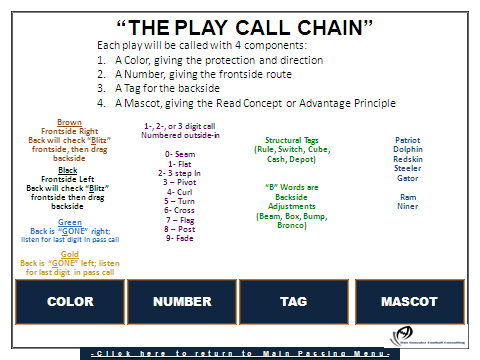

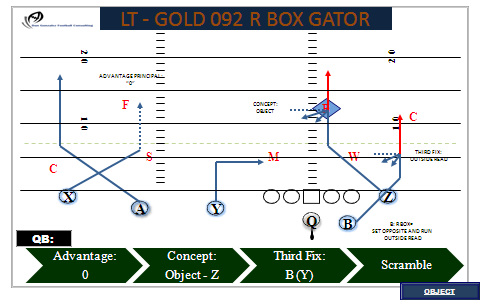

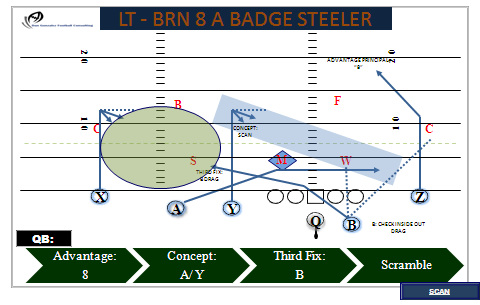

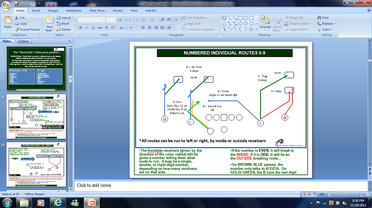

As the season moves along into every team's "crunch time", I am busy catching up with clients, watching games and practice clips, and offering suggestions where I can. Aside from the camaraderie and relationships, this is the part I really miss: the game-planning. Getting to specific problems and specific solutions with specific players in mind is always fun. For this reason, I've always loved studying NFL tape. While many have felt that NFL offenses were too homogenized, there are always been those who push the envelope. A highs school or a small college has more in common, roster-wise, with the NFL and than it does with a Division 1 powerhouse. I say this because a small college or high school's depth is much more similar to a pro team's roster - where the dropoff from a starter to a backup might be HUGE - in contrast to the revolving door of Parade All- Americans that can be found on top college rosters. Further - this year in particular - those who follow the NFL have seen an overarching effort in attacking defenses. More and more teams are in the no-huddle mode on a regular basis, and still deploying a full array of pass concepts. And while zone-read concepts are in play, they are used judiciously or not at all, because of the lack of depth at that position; this is certainly a concern in many high school situations I know of. In fact, I think the pendulum has swung, with "generic" spread systems being more prevalent at the COLLEGE level with little variety from team to team. I also think that for these reasons, the flexibility of the system we have in place allows us to take advantage of whatever physical match ups we can dictate. In the system described in "Recoded and Reloaded", I took the best ways I know of assigning pass routes, and sequencing them for the QB. For the purpose of calling pass patterns, we use a numbered route "tree" to call the frontside receiver's assignments. This innovation eliminates confusion when moving players within a formation -- one of the keys to dictating matchups. Much is said about "dictating matchups," yet I find it interesting that few systems allow for this without an inordinate amount of memorization on the part of the player. More importantly, these is a way to communicate WHERE THE QB PUTS HIS EYES. Getting people open on a pass play is of little importance if there isn't a corresponding way to have the passer ready to throw there in a given time. We accomplished this by designating Advantage Principles that isolate defenders, and Concepts that stretch those "2 on 1s". From there, we have "3rd Fix" outlets that break into the QB's vision. In our nomenclature, this is referred to as ACTS. Using these principles, we can dictate (from one play to the next) the thought process we feel will best deliver the ball to the intended receiver. We built a system of teaching in which "new learning" is minimized. Still, there are situations where some defenses required extra cues for the passer. In today's no-huddle environment, the old "catch all" of sending instructions in with a messenger is no longer an option; it is also poor form for a coach to ask a player to execute something he has never practiced before. These "cues" would be something similar to the navigation system in my car: I would have a standard route to follow (A.C.T.S.), but if there was an obstruction, the computer (the coach) could direct me to an alternate route. These "Navigation Tags" would fit right in with the normal mode of play calling, allow a coach to guide his passer mid-drive, and best of all, allow practical solutions that can be built into practice and can be called upon whenever the situation arises. Having this means of communication allows the offense to attack a defense to the fullest extent, without the benefit of a 14-year veteran QB. This allows one to be flexible with pass patterns, and can take advantage of a great plan on the part of a coaching staff. There are 3 Navigation Tags; for the purpose of brevity, I will give brief explanations, and go into depth with the FALCON tag. RAIDER - code for "Read Advantage to In/Under" We are telling our passer we want to take a look at the frontside throw through the coverage, but if not, go immediately backside to a High/Low we have built for you. When developing full-field pass patterns, defenses can overplay the frontside route, and recover on the backside. For us, an "UNDER" is any check release or short route holding the window open for the IN. DRAGON - in this system's use of half-slide protection, where the back checks frontside and drags backside on any of our Drag tags (below), "DRAGON" tells the QB to stay with the called crosser for an extra count, and go straight to the back's drag from there. In communicating, the call below would simply change to LT BROWN 8 A BADGE DRAGON. FALCON -- our code for "Flash At LOS; Otherwise - Normal." Here, we use a WHIP tag on the backside of a standard pattern. WHIP serves two purposes: first, it allows our QB (or coach) to signal a "press man beater" based on how the defense is aligned. Below, diagram 1 is a "rub" for #1, and #2 is a "rub" for #2. Second, the man setting the rub continues on an IN route, so that the passer has a completely intact pattern, from frontside to backside. Once the selection is made, the QB needs to confirm if the RUB is successful at the snap. If it is, he's letting the ball go. If not, he would use the same process he would on the given frontside pattern (471 is shown below). Once again, versus zone, the pattern still has the feature of a backside in as the Third Fix for the QB. Navigation Tags allow the coach to control where the ball goes based on the game situation, without the need to wait for a the next offensive series. These tags also hold the coach accountable to the game plan by giving specific instructions to the offense in the present tense. Most importantly, it removes much of the guesswork for the quarterback; it assures that the offense will be the "last to have the chalk" on a down-to-down basis.

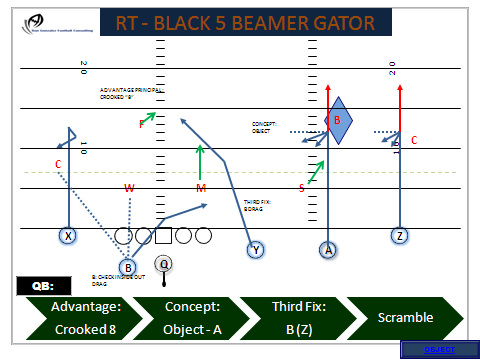

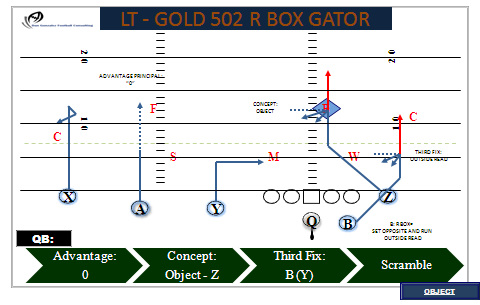

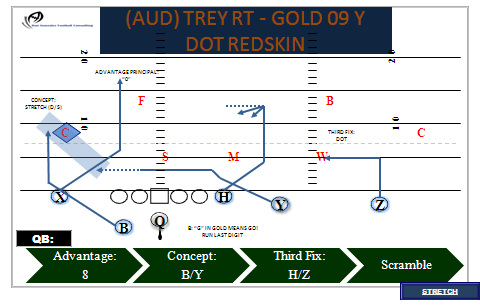

When I put out my second book in late February, it was a departure from the terminology I used when I was coaching. As I had previously mentioned, the impetus was an attempt to create a structure so that little guys (like the one below) can start learning real passing structures, as opposed to the trick play fest (that, or 1-receiver routes) many teams will run at this age. While most of the feedback I got was overwhelmingly positive, there were some detractors, expressing concerns that the pass system was not simplified. All I have seen is proof to the contrary. Despite being as green as you could be (only 2 of our 11 kids have played organized football before this summer), the progress has been outstanding. With just one initial installation meeting, the rules, route tree, and backside tags used were introduced. I made parent participation mandatory (which also gives them ownership and understanding, curbing questions like "why won't you let my son play quarterback"), and the basic nomenclature was laid out using the same PowerPoints seen here. The assimilation has been astounding! We used 2 of the 3 Advantage Principles, and have installed the following possibilities backside: - Rule - Switch - Drag - Slide (we are calling "half" - as a 5 yard in is half of the basic 10 yard in - Beam/ Box (backside streak reads and switched streak reads) Over the course of summer 7 on 7, we'd hit all 4 different advantage routes for scores (Flag, Seam, Post, and Hook), as well as Wheel, Drag, and Switch routes. Even more astounding is the availability of the THIRD FIX -- the principle that allows us to attack the full width and depth of a pass defense. When a group of 8- and 9- year olds can digest this, it is hard to give credence to claims by a few who think the system presented is "too advanced for high school players." Moreover, I keep getting notes like the one below, from one of my clients in Ohio: "Two years ago my staff and I went on a search for an offensive system that would help incorporate all of our schemes into an organized pattern and read system. We were lucky enough to find Dan’s first book and implemented his stuff into our program for the 2012 season. We finished with an undefeated season and over 5000 yards of offense. We changed all language and didn’t miss a beat. It is that simple. This past off season Dan’s new book Recoded and Reloaded really brought things together. Dan’s new book is as comprehensive, thorough and simple as they get. We have been lucky enough to have 5 straight All Ohio Quarterbacks at our place over the past 10 seasons. We have had a tremendous amount of team and offensive success over the years. Some coaches feel you shouldn’t mess with successful schemes. We believe you should continue to find better ways to do the things you do well. I can say without reservation we found that in Dan’s new book. Our skilled players have a much better understanding of the offense and our Quarterback has a complete understanding of his reads and progressions. We decided to have Dan fly up to Cleveland and spend a weekend with our staff. Dan is fantastic to work with and the whole weekend was spent on the passing game. We did not have to gut our offense and start from scratch. We found, in Dan, a way to re –language everything and have the ability to add in any of the best schemes at any time. I can tell you this, we have had several years with 5000 or more yards in a 10 game season and I feel we are more explosive in the passing game than ever going into camp this season. How the system uses advantage routes as a first progression has proven invaluable. In addition, the backside route system is fantastic. I find myself hoping the advantage route and the concept are covered so we can get to the third fix!! I would recommend his book to anyone searching for a complete system. Lastly, I would recommend having Dan come see you and your staff as he is a fantastic teacher. Five months later he is sending updates and texts as he develops new things. Great stuff!!" Matt Duffy Head football Coach Willoughby South High School The further my clients get into the teaching phase of this pass system, the more convinced I am that this structure of calling pass plays is superior to what I did previously. Many coaches are hesitant to make such a leap (overhauling a system that had worked so well for so long), but I felt like it was an opportunity to offer the teams and coaches I work with a “catch-all” system of passing that could be taught to literally any level of player, but could also attack a defense with virtually any pattern structure. Likewise, high school teams that have switched to the system have reported a great ease in installation, and have added their feedback to improve the overall system in general. Because of the frontside tree (seen by some as too cumbersome), we are able to make adjustments that bring not only flexibility, but minimize learning burden as well. In this post, we'll look at some very inexpensive (from the offense's standpoint, in this way of teaching) adjustments to the "Big 3" patterns in this offense: Stick, Verticals, and Drive. We first examine STICK: The diagram above represents the way I learned the play, with the backside “Glance” or “Quick Post” providing an individual Advantage Route, discouraging defensive rotation over the Stick/ Flat combination. This setup, however, had a “point of no return” when the passer chooses the glance; if he chose incorrectly, there was no way to get back to the stick/ flat combo. However, if we deepen the depth of the Stick, giving a receiver more ability to adjust, we can now give the passer the best of both worlds: Further, with the rules built in to our system, we can alter the QB’s thought process, without the need for a Sideline discussion in between series: The 9 is NOT an individual Advantage Route, and we can tell adjust the Z’s route when we don’t need him to be on a post. Because the passer’s eyes will be inside, there is no need for a post. Because of the system, we can adjust a receiver’s assignment without burdening memorization. Another example of a situation specific adjustment could feature this pattern in anticipation of tight man coverage: Another nifty adjustment that takes advantage of a team’s gifted option-route runner is seen below. Using the RAM principle, the W is always in a bind. A complete write up on this can be found. We are also able to incorporate the option route from 3-1 sets, utilizing the option route described above and mating it with the popular “Y Cross” pattern: Though this pattern isn’t technically a member of the vertical game, I included it in this article to give an example of how to attack a specific response by a defense. The changeup above specifically attacks a pass defense’s attempt to cover up the 3x1 Four Vertical pattern, with M and F riding the #3 and the S walling off the #2 receiver: Once again, our system can help a QB navigate the murky waters of a pass defense, and use Streak Read adjustments to or away from the 3 receivers. Keep in mind that the streak read is a univeral route in this system; the core routes of the offense are taught to all position groups so that there is no new learning when making such an adjustment. We are also able to “slow down” the locked seam for the QB, and try to manipulate the S who is taught to wall #2, once again with no added learning burden: This method of re-distributing rules on the backside also greatly aided the DRIVE pattern; the utilization of a THIRD FIX of the passer’s eyes frequently finds a receiver the defense cannot account for. Getting the ball to a drag route in a vacated flat area is a primary goal of the DRIVE pattern. Once again, we are able to attack defensive responses without increased learning burden, and without changing the picture for the QB: DOT is a tag that stands for "Drag with an Outside Two;" the "2" route enters the area that was previously occupied by the back. Since we are wheeling him to the frontside, this a cheap, easy way of creating the same look for the QB.

"Like I said before, if you werent in the room with Amos Alonzo Stagg and Knute Rockne, then you stole it from somebody" - Chip Kelly I like so many things about Coach Kelly's approach, but this quote might be what I like best. Football is a game of handed-down knowledge, and few coaches have had his recent success. Whether or not he continues that success with the Eagles is beside the point (I am interested to see how they handle personnel turnover, with released players singing with other teams and giving signal/ procedural information to calling the offense); his innovation is well documented, but the credit he gives to his past experiences is also apparent.

This made me start thinking about the people who I was lucky enough to learn from, and where different components of what I consider as "my" offensive system evolved from: - I learned John Mackovic's system as a college player. His system had its roots in Tom Landry's offense, as he was an assistant for him. The system contained everything, including KEY screens that are so much a part of today's spread environment. Also, as the Cowboys and 49ers dominated the NFC in the early and mid-90s, influxes of those passing games trickled into our own, using NFL film as a teaching tool. Multiple shifts, motions, and personnel groupings were a focal point of the attack. Cleve Bryant, my position coach, fostered my thirst for knowledge as he let me handle our passing game quality control. Gene Dahlquist (OC/QBs) was an excellent teacher of passing mechanics and the progression-based passing game. - My first boss, Kurt Nichols, taught me how to be in a single-back, 3-receiver environment on an every-down basis. I learned the constraints of the zone running game from a spread out environment. At the same stop, a former GA for John Jenkins, Wes Cope, taught me the inner workings of the Run & Shoot passing game. - My second post reconnected me with a former assistant at Texas, Jack Kiser. I will forever be endebted to Jack for feeding my thirst for knowledge; while there, he flew in both Norm Chow and the late great Mike Heimerdinger for clinic sessions. For any young passing-minded coach, these sessions were a dream come true -- I learned the BYU system verbatim, and 'Dinger's take on the staples of the West Coast Offense, and its evolution to one-back sets. Coach Kiser let me install the passing game, and this experience proved invaluable. - Along the way, Bill Mountjoy served as a constant resource. As I was trying to mold the axioms I beleived in into a system, much of the focus was on Joe Gibbs' offenses in Washington. This would not have been possible without Bill. Bill also introduces me to John McGregor, a longtime Henning assistant. No matter how crazy the idea, I could be assured of constructive feedback. Also, John helped use his connections to get all-access exposure to Mike Martz's Rams in their heyday, as well as Bruce Arians' translation of the Colts vaunted system. To this day, the exchange of ideas is constant. - At the age of 25, Phil Wickwar gave me total autonomy of an offense, as did Tommy Felty in my next job at 27. Our teams were a laboratory of sorts, and both these coaches gave me the authority to experiment as I saw fit. For example, our athletic dropback passer Billy Malone had two 80 yard runs on the zone read in 2000. It was during these stops where the vertical reads of the run and shoot were streamlined and rhythm became more defined to fit with the rest of our progression- based passing attack. The numbers advantage principle came to fruition in our "3" pattern - our version of the Run and Shoot CHOICE route. Moreover, an extended no huddle attack was used for the first time. - While at North Lamar, I corresponded with the late great Homer Smith. Always willing to answer questions and send me drill tapes, I will be forever grateful. He taught me the most in terms of using backside receivers and thus attacking with all 5 receivers on every play. - Though several years removed from college, my connections with my Alma Mater were still paying dividends. My friend and teammate, Todd Ford, began working for another Longhorn -- Todd Dodge. Coach Dodge's system and QB/WR methods are legendary in Texas, and being an annual coach at his camps exposed me to some tremendous knowledge. For example, I got to meet (among several others) Clayton George, who elevated the way I taught receivers. Also in this time, Greg Davis' openess to share his insight is evident in looking at my offenses. A former teammate of mine (former Texas QB and current MD Richard Walton) called Coach Davis the best teacher he has ever had. The UT record books reflect this as well. - At Lenoir-Ryhne, I met John Patterson, who encouraged my constant evolution in the passing game, and tirelessly searched for ways to protect for all the routes I was diagramming. In 2002, we boasted the league's leading passer and school record holder, Brett Meunier. It was during this stop when we began combining 3 step patterns with backside outlets that came open with 5 step timing -- blending some Run and Shoot ideas with Homer Smith's. Also, during the 2003 season, JP and I began developed a highly evolved read system to take advantage of our running QB, Scott Branton. In 3 seasons, three different QBs (Kurtis Koester was the third) posted top 10 passing seasons in the school's record books. - Also prior to the 2002 season, Steve Kragthorpe let me come up and sit in on meetings with the Bills. Drew Bledsoe had just been acquired, and on his way to a Pro Bowl season in Kevin Gilbride's newly installed system. Many of the Run and Shoot patterns were obvioulsy familiar; I did discover some protection adjustments that would pay dividends in the future, as well as the principle of always throwing away from the MLB as a means for throwing levels-type patterns this would go on to become our Mike tags in the first book and RAM principle in the second. Anyone who had followed the evolution of my passing system can see that the X's and O's didn't change from the first book to the next; the organization is the driver of change. Much of the language is my own, although the idea of numbering receivers on a side comes from Marty McClintock, who was the head coach at Borger High School in Borger, TX. My parents had moved to Borger during my college years, and Coach Mac was always accomodating enough to talk ball with me back then. Of course, none of this would have happened without my high school coach, Allen Wilson. He's the man who taught me how to win, how to have faith in the face of adversity, and how this game can influence the lives of many. None of the previous would have been possible without Coach Wilson. When I began my coaching career right out of college, I took my first job in part because of the opportunity to learn the ins and outs of the "Run N Shoot." I can honestly say that that single year I spent there impacted me, from a learning standpoint, as much as any time in my football life. I was already well-versed in the "West Coast" or "Pro Style" way of doing things (I really hate those labels!), but the 'Shoot literally changed the way I looked at throwing the football to this day. As I re-configure (as described in my previous posts) the METHOD in which the offense is delivered, I am, time and again, brought back to the fundamental reasons I *loved* the run and shoot offense to begin with: - An economy of concepts - Efficient teaching - Having an answer to the defense you are confronted with ON THAT PLAY, not the next play, when the defense has a chance to adjust - Balance, in the true sense of what it should be offensively From my first coaching stop, no matter what the presentation (the presence of TE/ H-Back/ Fullbacks, multiple shifting and formations), the foundation, principles of attack, and route structures -- all had it's roots springing from the Run 'N Shoot. There was, admittedly, the real danger of being considered for jobs in declaring my passing game to be "Run and Shoot" -- so I described my offense as a "multiple offense that blends quick-rhythm passing with the ability to adjust to coverages" -- I smirk as I type this now. :) As I go back through all the film and notes I've gathered from clients, study material from various offenses across the country, and update my teaching materials (such as the PowerPoint slides above), I inevitably come back to the notion that the Run and Shoot provides some of the simplest, most effective, and easiest to learn methods for attacking defenses. Many of the bedrock principles in the passing game I have used are rooted in the Run and Shoot; I'm going to spend the next few entries talking about my system, give a little historical background, and hopefully develop conversations discussing this and other sytems. Until then -- enjoy this clip of June Jones covering 60 Z GO.... HAPPY THANKSGIVING! |

AuthorLiving in Allen, TX and using this outlet to not only stay close to the game I love, but to help pass on what I have learned from some of the game's great coaching minds. Categories

All

Archives

July 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed